This summer, we asked readers to send us their climate change questions. A lot of those questions sat squarely under umbrella topics we expected: how climate science works, what individuals can do to prevent greenhouse gas emissions and what crazy technological solutions might actually be effective. We’ll be coming back to those later. But first, we wanted to address a different sort of question: Who is winning climate change? Sure, climate change is a very bad thing in a larger, existential sense. But are there animals and plants whose habitats will expand in a warmer world? Is there anybody who has figured out how to profit off the coming apocalypse? Won’t some places be nicer to live in than others? You wanted to know. We’re going to find out.

Matthew Kahn has dreamed about buying a climate change retreat. If anybody would know where to go, you’d think it would be an environmental economist who literally wrote the book on which cities will adapt to a warming world and how they’ll do it. But rather than investing in land that’s safe from the risks of coastal flooding, midwestern downpours and crippling drought — Kahn was thinking Bozeman, Mont. — he’s instead settling into a new job in Baltimore, a city that’s expected to be flooding daily by the end of the century.

When we asked for your climate change questions, we ended up with 20 different responses that were all asking a version of the same thing: Where should I move if I want to avoid the worst of it?

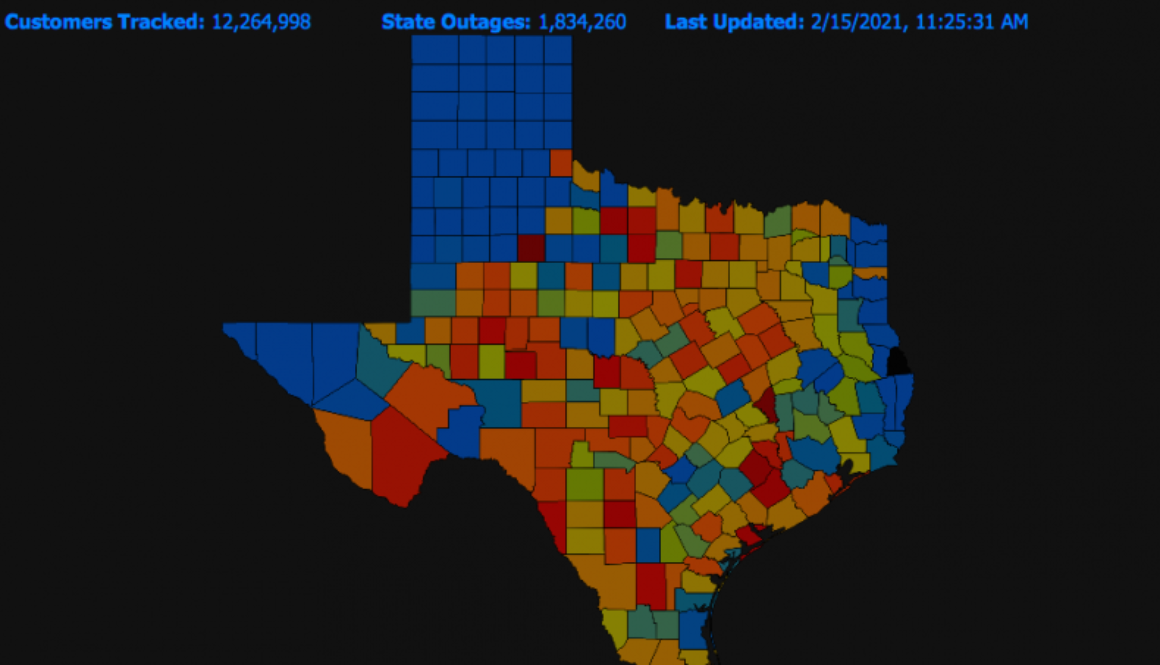

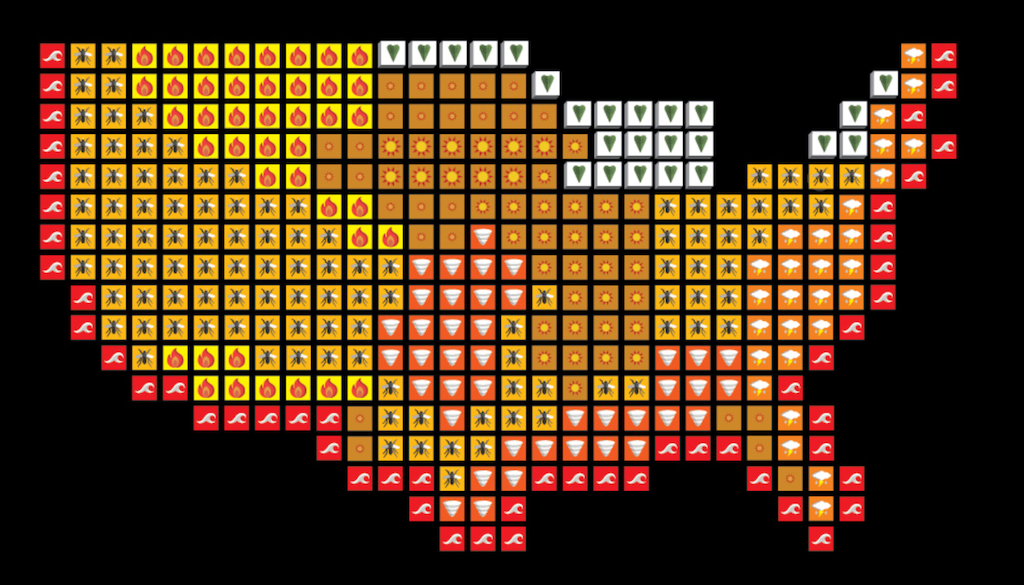

Turns out, finding a place in the U.S. that is benefiting from climate change is both easy and hard, researchers say. It’s not difficult to find the places at the lowest risk of experiencing the biggest hazards. Popular Science has mapped it using data from a variety of scientific research papers and risk assessment reports. Economists have mapped it based on projected changes in various quality of life indexes. Nonprofits are working on projects that will map it based on flooding risks.

But it’s one thing to look at these maps and start dreaming of your climate condo in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. It’s another thing entirely to say that it is a place you should move now. Or that the Upper Peninsula is necessarily going to “win,” just because in the long term it’s less subject to the negative side effects of a changing climate. The problem is one of both personal preferences and economics. We don’t all like the same weather. We seldom make investment choices on long time scales. We value things about our hometowns, other than whether they’re safe from a wildfire. It’s hard to predict which regions might win climate change when we don’t all agree on what “win” means.

“There are a couple of areas, in the short run, that actually improve,” said David Albouy, professor of economics at the University of Illinois. In 2016, he published a paper that compared the places Americans currently prefer to live with the predicted environmental change under global warming. In doing so, he produced maps of how quality of life might change in various parts of the country. “It’s still a generation away,” he said. But according to his estimates, Northern Minnesota, Seattle, Portland, Ore., and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan could all end up with more moderate temperatures and weather patterns than they currently have.

His maps, which include upstate New York and much of New England among the regions improved by climate change, somewhat align with estimates of the safest places to live made by mapping disaster risk alone. That’s especially true for the Upper Peninsula, a region fortunate enough to avoid increased risks of sea level rise, drought, tornadoes, hurricanes, wildfires and disease-carrying mosquitoes.

But despite the occasional trend story about coastal millennials moving to places that seem better positioned to ride out the ravages of climate change, there’s no real evidence that the Upper Peninsula is attracting new residents due to its climate prospects. In fact, nearly every county in the region has lost population in the last decade. Somebody found the place you should move. But nobody is moving there. So what gives?

That’s partly because real estate investing works at a different pace than climate change does, Albouy and Kahn told me. The maps that show the Upper Peninsula winning against other parts of the country are forecasts of the year 2100. “But why does it matter that [the value of the land] will go up in 100 years?” Albouy said.

Even coastal Florida, a region that’s been repeatedly affected by rising sea levels and storm surge from hurricanes, hasn’t yet seen a decrease in property values, said Matthew Eby, founder and director of First Street Foundation, a nonprofit that’s attempting to improve and expand flood risk mapping in the United States. The value of those homes aren’t rising as fast as homes further inland, he told me. His modeling suggests hundreds of millions of dollars in lost appreciation value. But the prices are still rising, and coastal property continues to be worth more than inland property. Just as climate scientists have long warned about the way climate change’s slowly raising stakes make them easier for politicians to ignore, real estate investors are also subject to the frog-in-a-pot-of-boiling-water problem.

That’s not the only reason there’s not a run on real estate in Sault Ste. Marie, Mich., however. Let’s back up to the study that Albouy published. His approach was based on calculating the financial drawbacks Americans are willing to put up with in exchange for pleasant weather today. For instance, wages are basically average in Hawaii and the cost of living is exceptionally high. But lots of people live there anyway. “Why? Because the weather is perfect,” he said.

But here’s where spotting the climate winners gets tricky, Albouy told me. When people talk about the best place to move to avoid climate risks, he thinks they’re usually thinking about places that are currently too cold becoming, well, more like California and other parts of the country in which Americans are willing to take economic losses in order to enjoy today.

But that’s not how climate change works. Michigan is getting warmer and wetter, but it’s still colder than Albouy’s calculations — or 30 years of data on American internal migration — suggest Americans really want it to be. Meanwhile, climate change tends to exacerbate extremes and increase the risk of probabilistically rare disaster events — things that don’t really make a place better even if they make it warmer. Imagine a Chicago with winters that aren’t much different than they are today, but summers that are more like those of Memphis. “Climate change doesn’t deliver quite the climate change they’d like to see,” he said.

Even if it did, Kahn said, there are all kinds of incentives — both social and economic — that make staying in a riskier region attractive. Consider the citizens of New Orleans, who have for generations known their city was prone to flooding and saw rising sea levels for years before Hurricane Katrina. Research since that disaster has shown that survivors who were displaced by the storm ended up making more money in their new cities. So why not move sooner? New Orleans had their families and their communities, and moving itself is expensive, Kahn said.

In the end, leaving a risky city before you have to might not look like a great option, even if you stand to economically benefit in the long run. If your climate “win” is at odds with where your family and friends are, it might not actually be a win.

Maggie Koerth is a senior science writer for FiveThirtyEight.